The Embarcadero, the six-lane, tree-lined boulevard along the waterfront that replaced the Embarcadero Freeway in San Francisco, in many ways epitomizes the freeway-to-boulevard movement.

The freeway, which separated downtown from the waterfront, was completed in 1959 as part of an intended freeway system connecting the Bay and Golden Gate Bridges. However, San Francisco’s “Freeway Revolt” left it as a one-mile connector to the North Beach and Chinatown areas, carrying 60,000 cars a day at its peak. The freeway was closed after being damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, and demolished in 1991 over the objections of merchants in Chinatown. Now a “complete street”, serving not just 26,000 cars a day but pedestrians, streetcar riders and other modes of traveler, the Embarcadero has made the waterfront an attractive destination for tourists and locals alike.

The freeway, which separated downtown from the waterfront, was completed in 1959 as part of an intended freeway system connecting the Bay and Golden Gate Bridges. However, San Francisco’s “Freeway Revolt” left it as a one-mile connector to the North Beach and Chinatown areas, carrying 60,000 cars a day at its peak. The freeway was closed after being damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta Earthquake, and demolished in 1991 over the objections of merchants in Chinatown. Now a “complete street”, serving not just 26,000 cars a day but pedestrians, streetcar riders and other modes of traveler, the Embarcadero has made the waterfront an attractive destination for tourists and locals alike.

Although the boulevard is broad, it is designed for pedestrians, bikes, and transit riders, as well as vehicles, and has provided a connection to the waterfront and the restored Ferry Building. And while about half the traffic on the former freeway was diverted onto alternate routes, traffic was successfully absorbed without disruption.

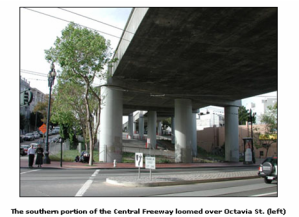

San Francisco’s Central Freeway removal, creating Octavia Boulevard, also illustrates how a freeway to boulevard project can transform a neighborhood.

Like the Embarcadero Freeway, the Central Freeway was completed in 1959, envisioned as part of the larger freeway system stopped by a citizen-led “freeway revolt” in the 1950’s and ‘60’s. At its peak, Central Freeway carried approximately 100,000 cars a day. Damaged by the 1989 earthquake, a segment of the viaduct was demolished, and engineers began planning a rebuild of the remaining freeway. However, citizens and local officials began to consider alternatives; when roadwork closed a segment of the remaining viaduct for four months without causing the anticipated gridlock, a surface boulevard concept gained favor. In 1999, residents voted for the boulevard alternative over the freeway retrofit and the freeway closed for good in 2003.

Like the Embarcadero Freeway, the Central Freeway was completed in 1959, envisioned as part of the larger freeway system stopped by a citizen-led “freeway revolt” in the 1950’s and ‘60’s. At its peak, Central Freeway carried approximately 100,000 cars a day. Damaged by the 1989 earthquake, a segment of the viaduct was demolished, and engineers began planning a rebuild of the remaining freeway. However, citizens and local officials began to consider alternatives; when roadwork closed a segment of the remaining viaduct for four months without causing the anticipated gridlock, a surface boulevard concept gained favor. In 1999, residents voted for the boulevard alternative over the freeway retrofit and the freeway closed for good in 2003.

Octavia Boulevard opened in 2005 with four center lanes for through traffic, landscaped dividers, two side lanes of local traffic and two lanes of on-street parking. The surrounding residential neighborhood has been transformed, green space added, new housing units are planned, and commercial property values in the area have increased. While the boulevard is still heavily used as a through route, traffic in the corridor dropped by half, as some of the traffic moved to alternate routes with sufficient capacity to handle the displaced traffic, and a small percent of drivers switched to transit.

Octavia Boulevard opened in 2005 with four center lanes for through traffic, landscaped dividers, two side lanes of local traffic and two lanes of on-street parking. The surrounding residential neighborhood has been transformed, green space added, new housing units are planned, and commercial property values in the area have increased. While the boulevard is still heavily used as a through route, traffic in the corridor dropped by half, as some of the traffic moved to alternate routes with sufficient capacity to handle the displaced traffic, and a small percent of drivers switched to transit.

While it was the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake that ultimately led to the demolition of the Embarcadero and Central Freeways, it was rejection by the citizens and Board of Supervisors of the original 1955 freeway plan that kept San Francisco from becoming an automobile-oriented city in the first place. As the city began building the Embarcadero along the waterfront, and residents could envision the effect of the full freeway construction plan on neighborhoods and businesses, a powerful opposition movement emerged. The neighborhood quality of life and economic development priorities that fired opposition in the 1950 and 60’s, came into play again in the decisions in the 1990’s to reject the rebuilding of high-speed expressways through the city.

Posted by oclblog

Posted by oclblog